Our History

Explore the history of the EFCA

The Free Church movement began in the Scandinavian countries of Sweden, Norway and Denmark.

The religious roots of the movement are firmly planted on the Word of God and on the foundational doctrinal truths of the Reformation. As such, the Free Church movement is considered a reform movement—not something new and disconnected from the past.

Drawing from the 16th-century Protestant Reformation, the Free Church adhered to the five revolutionary principles of the Reformation: Sola Scriptura (Scripture alone), Sola Gratia (grace alone), Sola Fide (faith alone), Solus Christus (Christ alone) and Soli Deo Gloria (to God alone be the glory). These principles laid the foundation for spiritual renewal and formed the basis for the movement during the next 250 years.

16th Century: Reformation in Scandinavia and Pietism

The Lutheran Reformation reached Scandinavia, which had been, as most of the rest of this part of the world, Roman Catholic.

The pulpit and preaching became more prominent in the churches. Elevated pulpits were added in churches to preach the gospel to the people. Instruction in Luther’s catechism became a regular part of parish life.

In Germany, as in other places, the good of the Reform, theologically, ecclesiologically and pastorally, had resulted in dead orthodoxy—sacramentalism, confessionalism and endless theological disputes. Being orthodox in belief did not make a difference in life.

In response, Johann Arndt (1555–1621), a German Lutheran theologian, wrote True Christianity. Arndt’s response and approach became known as Pietism, which emphasized regeneration, the need to be born again.

Philip Jakob Spener (1635–1705), another German Lutheran theologian and central figure in Pietism, followed Arndt’s teaching and promoted reform through collegia pietatis, a group of devout believers who would meet privately for prayer and Bible study. His work Pia Desideria, or Heartfelt Desire for God-pleasing Reform, became known as the classic statement of Pietism and presented a devotional work and textbook on church renewal.

Like the initial spread of the Reformation to Scandinavia, this Pietistic response to the Reformation also had a major influence in these countries. Although all of the streams of the Reformation influenced the Free Church, the church’s history is most closely connected with this Lutheran stream and its reformed elements.

17th–18th Centuries: Moravians, Pietism and Missions

Moravians led by Nikolaus Von Zinzendorf (1700–1760) practiced a Pietism that was motivated by missions and began influencing the Scandinavian countries of Norway, Denmark and Sweden. They brought an emphasis on a new birth in Christ and a living faith. Moravians organized conventicles—small, unofficial and unofficiated religious meetings of laypeople in homes.

These conventicles spread Pietism through the readers’ movement, which promoted reading the Bible and devotional works, gathering as believers in the first few free churches, being born again as the “one thing needful,” celebrating the Lord’s Supper as a rite for believers only, and meeting to pray for and send missionaries.

From this, the Free Church movement began to organize around the importance of meeting together with other Christians to read the Bible, to pray and to engage in mission outreach.

19th Century: Anglo-American and Trans-Atlantic—Early Evangelical Impulses

Anglo-American influences entered Scandinavia in the 1800s, which broadened perspectives beyond the Lutheran confessionalism expressed in the writings of The Book of Concord (originally published in 1580). The Anglo-American influences came from Baptist, Methodist, Dispensationalist and American Revivalist movements, rooted in the Puritan-Pietist revival traditions of Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), George Whitefield (1714–1770) and John Wesley (1703–1791), which emphasized the Bible’s authority and the need to be born again.

The Free Church movement was birthed in revivals in throughout America, Great Britain and Scandinavia as the gospel was preached and God the Holy Spirit transformed lives.

In Scandinavia, these new believers were part of the state church, Lutheranism, which for many had become dead spiritually, similar to the condition in which Pietism was originally birthed. Although believers remained in the church, people began joining readers’ groups, where they could gather outside of the local church setting to read Scripture together, sing and pray.

Many began preaching societies, which raised up several leaders. In Sweden, Peter Paul Waldenstrom (1838–1917) was an early leader of the Swedish Covenant, and Gustav Adolph Lammers (1802–1878) helped form the Christian Apostolic Free Congregation in Skien, Norway.

19th Century: American Evangelicalism and Early Free Church Influences

In 1873, Dwight Lyman Moody (1837–1899) and Ira D. Sankey (1840–1908), his musical partner, began a two-year series of revival meetings in Great Britain. When they returned to America, they were international heroes.

Moody promoted the following: mass evangelism meetings with after-meetings to win the “anxious” to faith; evangelical, non-sectarian cooperation; lay evangelism; gospel music; Christ’s second coming with a rapture; and an independent congregational church. Free church pioneers sensed in Moody a kindred “free” spirit and increasingly adopted his beliefs and methods, characteristic of this new American evangelicalism.

Believers in the Free Church movement, often referred to as Mission Friends, shared Moody’s beliefs in the authority of the Bible; conversion as the “one thing needful”; God’s love at the cross; lay evangelism; and living faith and piety. Even more so, they maintained their own distinguishing beliefs, including the evangelical-alliance ideal, new premillennialism, after-meetings, independent churches and the importance of Bible courses and institutes.

Several notable Mission Friends were used by God in the early days of the Free Church in America, including Paul Petter Waldenström (1838–1917); Fredrik Franson (1852–1908), a co-laborer with Moody; and John Gustavus Princell (1845–1915), founder of the Swedish Evangelical Free Mission.

Fredrik Franson was particularly influential during this time period. He had similar convictions to Moody and became proficient in Moody’s methods of leading inquiries to faith, especially during the after-meetings. He became known as “Moody’s Swedish disciple.”

In 1878, Franson was sent out as the first missionary from Chicago Avenue Church, where Moody served as the pastor. The following year, in 1879, Franson cast a vision for an outreach to Utah among Swedish Mormons. In 1880, he planted Swedish free churches in Denver and Nebraska, and overseas, he planted churches with the Free Church associations in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Germany. In 1890, he founded the Scandinavian Alliance Mission, today known as TEAM (The Evangelical Alliance Mission).

Thanks to the Lord working through Franson and many other leaders like him, by the 1880s, Scandinavian Free Church people in America were committed to a shared orthodoxy and orthopraxy: the authority of the Bible, the Trinity, the atoning death of Jesus, salvation by grace through faith, new birth, the Second Coming and the autonomy of the local church. On minor doctrines, they followed the dispensational view of the Second Coming, the Congregationalist view of the church as independent but cooperative and a Wesleyan emphasis on holiness.

20th Century: Free Swedish and Dano-Norwegian

In 1884, 22 Swedish free church ministers gathered in Boone, Iowa, to discuss the nature of the church and initiate cooperation to support home and foreign missions. Historically, this is considered the beginning of the Free Mission work of the EFCA.

The next year, in 1885, ministers gathered in Rockford, Illinois, to discuss the ministry of the Holy Spirit and the cooperative home mission to Swedish Mormons in Utah. They decided to support the work of Ellin Modin and Edward Thorell. In 1887, the Swedish Free Mission work commissioned the first overseas missionary, Hans Jensen von Qualen (1848–1915), a Dane, to Canton, China. Prior to this, while in Chicago, von Qualen met Eugene Sieux (Yu Chi Siu) (1866–1946) and John (Yuen) Lee. After Lee’s conversion to Christ, the three of them were of one mind to bring the gospel of Jesus Christ to South China.

In 1890, the “Free Mission Friends” approved bylaws and adopted the name Swedish American Mission Society for Home and Foreign Evangelistic Work. Their stated purpose read: “The purpose of this Society shall be, to the extent of needs and resources, through sending and supporting of well-regarded missionaries and preachers, to promote the spreading of the gospel in this and other countries.”

Although the churches were reluctant to form a denomination, with all the machinery that would entail, they saw clear reason to work together interdependently, especially in areas of global outreach, pastoral training and church planting.

In 1891 Norwegian leaders from the midwest and west met in Chicago to form the Western Association to promote ministry and fellowship, and in 1898, churches in the east formed the Eastern Missionary Association for similar purposes.

Amid these mission-sending efforts, a ten-week biblical course was offered in 1897. By 1901, this educational effort became the Swedish Bible Institute, founded to train men and women for ministry and missions. This Institute is now known as Trinity International University.

By the early 1900s, the Swedish and Norwegian-Danish Free Churches had developed formal partnerships. Both local church autonomy and a broader association to a larger movement were important, yielding an interdependency with other churches of shared biblical faith and practice. Leaders in the Free Churches recognized the strengths of associating with other like-believing and like-hearted churches and expanding their ministries, especially in the areas of missions, the ordination of pastors and ministers, and biblical and theological education.

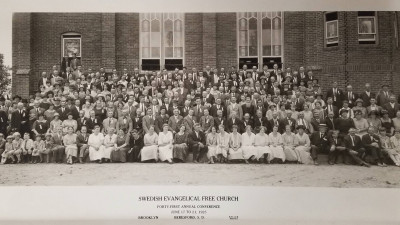

In 1908, the Free Mission incorporated in the state of Minnesota as the Swedish Evangelical Free Church of America. The merger between the two Norwegian-Danish associations occurred in 1912. A Statement of Faith was prepared, and the Norwegian-Danish Evangelical Free Church Association incorporated with 20 congregations. They partnered with the Scandinavian Alliance Mission (TEAM) in the sending of their missionaries.

The two Scandinavian church bodies grew well over the next few decades. More churches were added and district associations were formed, allowing close partnership with other churches in their geographic areas.

Although the founders of the Free Church movement had wanted to avoid forming a denomination, it was becoming apparent that some kind of central office was needed. In 1922, after years of being led by several superintendents of Mission, Erik Anton Halleen was officially chosen as president of the Swedish body, serving for thirty years. The Norwegian-Danish group had several part-time leaders during the same time period.

By 1920, the Overseas Mission had added Venezuela as its second field, led by David Finstrom, and a few years later, Titus Johnson opened the new field in Congo. By 1950, the mission had a presence in Hong Kong and Japan as well.

Each body developed its own publication ministries. The Swedish group used the Chicago-Bladet, a newspaper originally published privately by John Martenson and later purchased as their official platform. In 1931, they started the Evangelical Beacon as an English publication, which served as the official periodical until 2003. The Norwegian-Danish body also published a periodical called the Evangelisten.

In both groups a ministerial organization was developed to serve for the encouragement and training of pastors, including ordination and credentialing. Later, the Committee on Ministerial Standing took on these important roles.

Evangelism remained a priority in the early 20th century. Most churches had regular week-long revivals, often led by traveling evangelists, both men and women. In the warmer weather, the revivals were often held outside under large tents.

Sunday School and other children’s programs were also widely adopted as both groups recognized that the future of the church was in the next generation. Various districts developed youth conferences, and in 1941, the Free Church Youth Fellowship was started at a national level.

By the 1940s, the two Scandinavian groups were talking formally about the possibility of a merger. Toward the end of that decade, their respective Bible institutes had merged on the Chicago campus and assumed the name Trinity. Soon after, the publications departments began working together and united their operations.

20th-21st Centuries: Evangelical Free Church of America

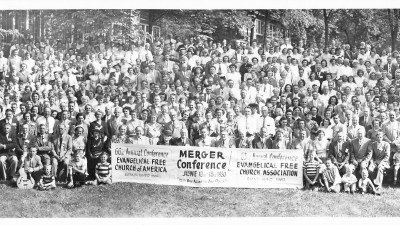

In June 1950 at the Medicine Lake Conference grounds near Minneapolis, Minnesota, a historic conference celebrated the merger of the Norwegian-Danish Free Church Association, comprised of 78 congregations, and the (Swedish) Evangelical Free Church, made up of 197 congregations.

The Evangelical Free Church of America (EFCA) was born. Together, these 275 congregations reported a combined membership of about 20,000 people.

At the heart of this merger was a commitment to a twelve-point Statement of Faith, emphasizing such evangelical theology as the inerrancy and authority of the Scriptures, the Trinity, the full deity and humanity of Christ, humanity being sinful and in need of salvation in Christ, and eternal conscious punishment for the unbelieving, among other critical doctrines. The Statement of Faith also included some distinguishing Free Church beliefs, such as local church autonomy and a premillennial and imminent return of Christ, with doctrinal roots tracing back to the American evangelicalism espoused by Moody and earlier leaders.

E.A. Halleen served as president of the joint body for two years, until his retirement, when Arnold T. Olson, the leader of the merger initiative, became president of the merged EFCA in 1952.

The decades after the merger tell a story of remarkable growth in the districts, with hundreds of new churches being added. New fields were added overseas so that by 1984, the EFCA had 245 missionaries in twelve countries. Trinity had outgrown its Chicago campus and moved to Deerfield, Illinois.

Dr. Thomas McDill was elected president in 1976 and served until 1990. Under his leadership, the EFCA grew to over 1,000 churches.

At the centennial EFCA conference in 1984, EFCA President McDill issued a challenge for the EFCA to become a more ethnically diverse denomination, not only reflecting the ethnic demographic in America, but even more so reflecting the end-time gathering of a those purchased by the blood of the lamb “from every tribe and language and people and nation” (Rev. 5:9), the gospel bearing fruit in the here and now of the church of Jesus Christ.

Dr. Paul Cedar succeeded Dr. McDill and led until 1996. Bill Hamel became president in 1997 and served until 2015. The number of EFCA churches at that time were nearing 1,200, including a presence in 40 mission fields around the world with some 600 missionaries serving. President Hamel worked hard to develop ministries among under-represented groups, including African-American and Hispanic believers. During this time, the Crisis Response ministry was formed to help churches with disasters, earthquakes and fires.

In 2008 the Conference of the Evangelical Free Church of America adopted a revised and strengthened ten-point Statement of Faith, and in 2019, the Conference adopted a one-word change to Article 9, Christ’s Return, of the 2008 Statement of Faith, removing the word “premillennial” and replacing it with “glorious.”

Rev. Kevin Kompelien served as president from 2015 to 2023 and was followed by Carlton Harris, serving as acting president.

From these humble beginnings, a Free Church fellowship flourished, representing a movement that today consists of almost 1,600 churches in America and ministries around the world. True to its theological foundations, the EFCA remains passionate about the mission to glorify God by multiplying transformational churches among all people.

This text is adapted from “Appendix Four: EFCA History: A Brief Overview” in Evangelical Convictions, 2nd edition.

For more EFCA history, see the following resources:

Get the EFCA Update

A biweekly round-up of news, events, resources and stories from the EFCA.